The Beauty of the Old - Marc Hoch

Does it always have to be a Summilux, a Noctilux or a Canon Dreamlens? On the distinctiveness of old lenses.

When lenses are judged, sharpness is almost always the central criterion. Many experts and enthusiasts, especially in the Leica context, idolize them and proudly display hugely zoomed-out areas of a photo. They enlarge the outermost corner of a landscape shot and show how a single tree has been magnified a hundred times by the lens. Of course, this has nothing to do with photography, and nothing is more boring than sharpness. Or to put it another way: if the picture isn't good enough, sharpness doesn't help to make it better. Even a boring sharp picture is a boring sharp picture.

For some years now, a second criterion has therefore become established in the assessment of lenses: "character". As with people, "character" refers to everything that is special - and this is often not the perfect, beautiful, positive, but the imperfect, angular, non-flattering. Leica enthusiasts, whose passion goes beyond all measure, are particularly looking for these characterful lenses - and the more expensive they are, the more willing they are to forgive their faults, and even more: they quickly declare everything that is a disaster from the perspective of sharpness to be art.

Let’s take the Canon 0.95/50 - a lens that is incapable of drawing even a single millimeter "sharply" at full aperture. This weakness is declared a strength, it has been considered a "Dreamlens" for years. Or the Zunow 1.1/5cm for Leica - three times more expensive than the Canon. If you use it to photograph a cab sign in the evening at f/1.1, for example, you will hardly be able to read the letters - because the Zunow is probably the most light-sensitive lens of all time. Nevertheless, enthusiasts say that it is "luminous and soft" at full aperture.

Both lenses are very fast, and in fact it is the large apertures that give all lenses their character. However, those who strive for this distinctiveness, who want a special image in this way, do not need to spend thousands of euros - there are cheaper solutions - and that is what we will be talking about here.

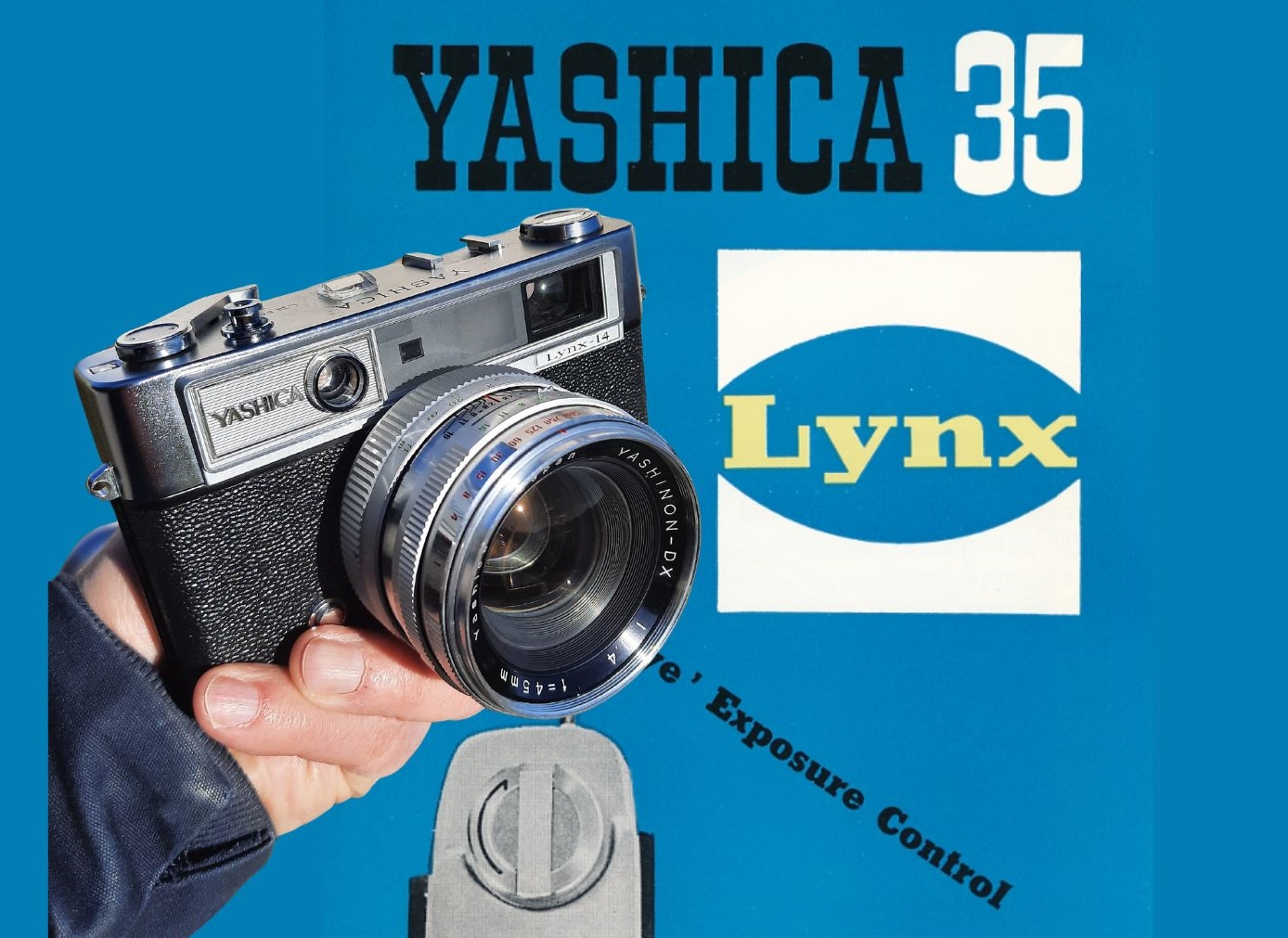

We would like to present four lenses here that have rarely been considered in the competition for the lens with the strongest character: the Sonnar 1.5/5cm in a pre-war and post-war version, the Xenon 1.5 and the Nokton 1.5/5 cm. All lenses have a high speed in common and all have a Leica M39 mount. But are they also from Leica? Of course not! The Sonnar was made by Zeiss, and we expressly do not want to enter into the eternal controversy here as to whether these lenses were originally built by Zeiss for Leica. They do exist, and not even a few, and we can be sure that most of them were assembled like little Frankensteins for Leica in private workshops after 1945.

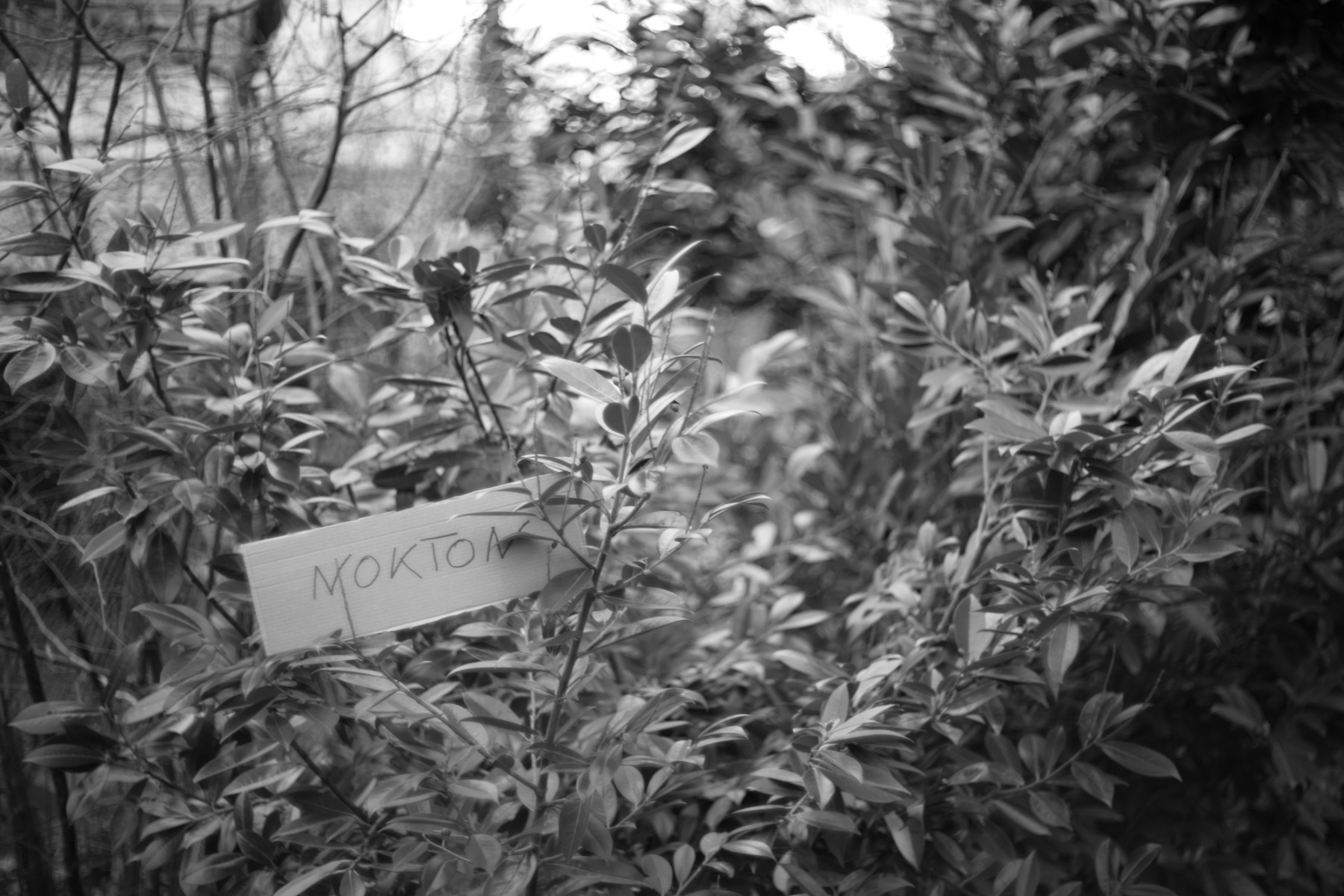

For the Xenon and the Nokton, things look a little different: The Xenon was originally calculated by the British company Taylor-Hobson, and Leica "somehow" further developed the British patent with Schneider (a mystery!) and then stuck its glorious logo on it: a tradition that continues to this day in Wetzlar with other companies. At the beginning of the 1950s, the Nokton was produced by Voigtlaender, a very successful company at the time - actually for their own cameras, but also in very small numbers with an M39 mount for the competition from Wetzlar. The Nokton, we'll say it right away, is a fantastic lens whose history and variants are still far too little researched.

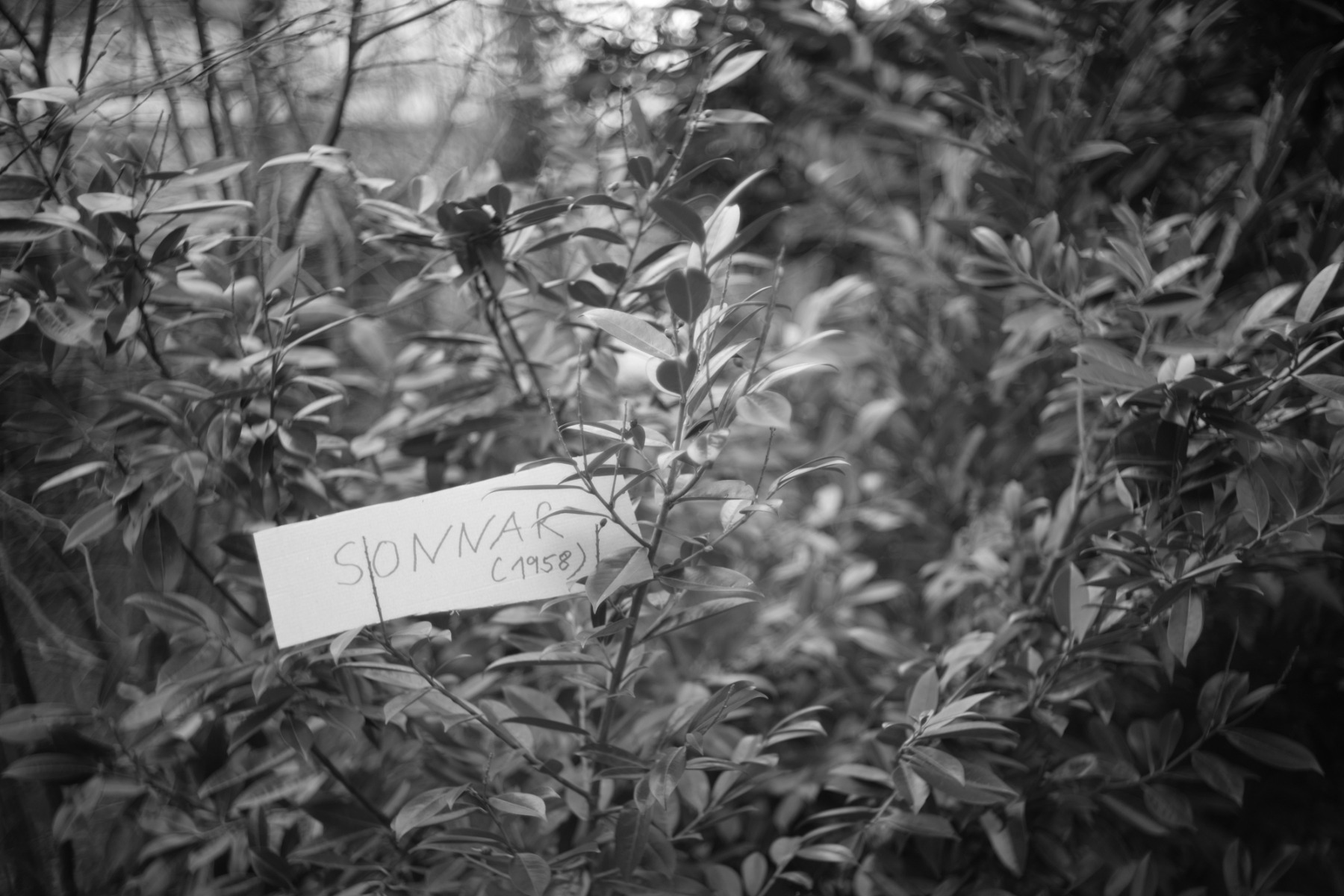

Let's get to the results and make a few basic statements about the appearance. Xenon and Nokton are beautiful lenses, heavy and shiny, a pleasure for the eyes and hands. The Sonnar-lenses, on the other hand, look like a GDR car against a Mercedes. This is especially true of the lens manufactured in 1958 at the Zeiss factory in Oberkochen - a miserable thing to operate, as everything clunks and slips. Leica aficionados turn away in horror.

Click to enlarge

Xenon Nokton

The pictures we show here have not been processed, but come directly from a Leica SL(black and white jpegs). What is the first impression? Of course, it is immediately noticeable how low-contrast the Xenon and the 1942 Sonnar in particular are. Even the slightest backlighting gives the image something milky and bright - similar to the Summilux 35 steelrim, only this 10,000-euro lens is referred to approvingly as "glow". Let's say with respect to the steelrim fans: the Xenon and the Sonnar 1.5 have too much glow at full aperture, and their blurring does not quite reach the level that we could speak of a "Dreamlens" as with the Canon 0.95 - the Sonnar from 1942 in particular is still too sharp for that (although of course it is not sharp at all). Contrast and sharpness are far better with the Nokton and the later Sonnar from West Germany - the Nokton is clearly ahead. In general, the Nokton is a top-notch lens - its bokeh at night is unique, its sharpness is sufficient, the gradient is as smooth as butter.

Unfortunately, no one has yet coined a slogan for this wonderful lens - otherwise it would have long been as well-known as the Bokeh King, the Dreamlens or the Blubber Trioplan and would have to be three times more expensive. By the way: There are very good adapters from Amedeo Muscelli: This allows a Prominent Nokton, which was built by Voigtlaender for the Bessa cameras, to be adapted for a Leica M camera. This is of course much cheaper.

Finally, let's come to something obvious: the old lenses were not designed for the super high-resolution sensors of digital cameras. In an old film camera and with a black and white Agfa film, these lenses look completely different, as the following sample photos should show. Who wouldn't say: Man, these are damn beautiful!

Click to enlarge

Xenon Nokton

Marc Hoch