Review: Nikon Reflex Nikkor 2000mm F11

This Blog post was written by Juza Yossarian, who has also reviewed other Superteles like the Canon EF 1200mm f/5,6 USM about one year ago. You will find this and many more interesting content in our Blog section.

Review: Nikon Reflex 2000mm F11

The Nikon Reflex 2000mm f/11 is the longest focal-length lens Nikon has ever produced. It was presented as a prototype at Photokina in 1968 and entered production in 1970. It is a massive catadioptric lens: to achieve the incredible focal length of 2000mm while keeping the physical length within a “reasonable” range, the only solution was a mirror system. Even so, we are speaking of an optic that is 60 centimeters long and weighs a hefty 17.5 kg — or even 25 kg with the dedicated gimbal head.

I was lucky enough to personally test an extremely rare example of this lens at Jo Geier’s Mint & Rare in Vienna, a specialist shop for historic and collectible lenses and cameras. I will tell you the story of this lens, and — for the first time — you can also see photos taken with the Nikon Reflex 2000mm f/11!

“The handheld shot with the lens has by now become a tradition in every ultra-tele test :-)”

The History of the Nikon 2000mm

We travel back more than fifty years, into a golden age of optical development: the 1960s and 70s brought forth some of the most extreme lenses ever built. They were never intended to achieve high sales numbers, but rather to demonstrate technical capability — products meant to inspire dreams and be displayed with pride at trade fairs and in catalogs.

Nikon had already developed a 1000mm f/11 catadioptric lens in the early 1960s; in the following decade, the 2000mm debuted, alongside the 6mm f/2.8 fisheye. Around the same time, Canon introduced the Canon Mirror TV 5200mm f/14, a colossal mirror lens weighing over 100 kg, along with an 800mm f/3.8. Zeiss joined the race as well with the Zeiss Mirotar 1000mm f/5.6, also based on mirrors and similar in size to Nikon’s 2000mm f/11.

Today, most lenses are designed to be light, compact, and efficient; these “ultra-telephotos” of the past are the complete opposite of rational and practical optics — and precisely for that reason, they possess an incomparable charm.

Back to our Nikon: it is a lens with a very simple optical construction — 5 elements (3 lenses and 2 mirrors) in 5 groups — in stark contrast to the 20 or 30 elements found in modern supertelephoto lenses. Of course, extreme sharpness wasn’t required back then, as the “sensor” was merely film (with relatively coarse grain by today’s standards). And even if one had desired it, the technologies for such complex optical designs simply didn’t exist at the time.

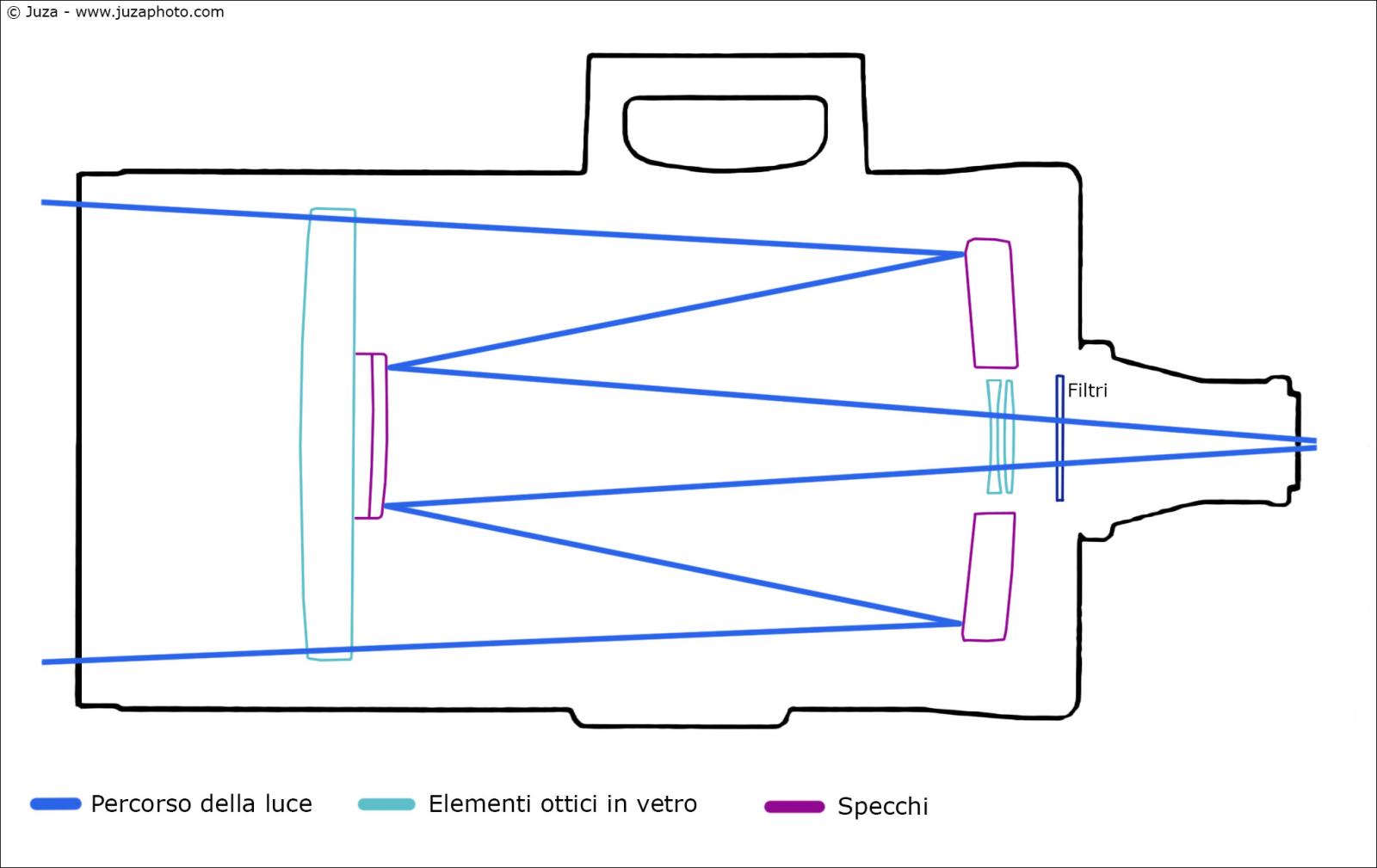

It is a catadioptric, i.e., a mirror lens: this means that a large portion of the front element is obscured by a mirror (facing inward and mounted onto the front element). The term “Reflex” in its name refers to this mirror design — not to SLR cameras. Light enters through the unobstructed portion of the front element — effectively a ring — hits a secondary mirror at the back of the lens, which throws the light onto the primary front mirror, and finally the light passes through the remaining optical system and reaches the camera.

As we can see in the illustration above, the light bounces between the mirrors of the 2000 mm, allowing an extremely long focal length to be achieved with a reasonable physical length. The optical diagram shown above is that of the 2000 mm, but the principle illustrated applies to all catadioptric lenses. As a point of interest, this five-element design is identical to that of the Nikon 1000 mm f/11: Nikon first developed the 1000 mm, a much smaller and more affordable lens that today can be found on the used market for around 400–500 euros; for the 2000 mm they “simply” doubled the size.

This forward-and-backward light path allows a lens only 60 centimeters long to provide a focal length that would physically require about three times the length — roughly one and a half meters in this case. On the other hand, an adjustable aperture mechanism is impossible; the aperture value is fixed in all mirror lenses and corresponds to the shape of the front element. Since the front element is ring-shaped, the bokeh in out-of-focus areas adopts this shape as well: catadioptric lenses therefore have a very distinctive — and often unflattering — out-of-focus rendering, where all point highlights turn into rings. The bokeh only becomes pleasant when the background is very uniform and soft; otherwise, it grows harsh and unattractive.

Since the aperture cannot be adjusted, some mirror lenses use ND filters to reduce exposure in bright light; with the Nikon 2000mm this is unnecessary, as f/11 is already relatively slow (though remarkable for this focal length!). Nevertheless, the lens incorporates a built-in filter system — not for brightness control, but for tonal adjustments in black-and-white photography: it offers three color filters (yellow, orange, and red) for altering tonal rendition when using monochrome film.

On the left, the effect of the various filters (shot with a modern digital camera); on the right, the result that would be obtained with black-and-white film

Focusing is, of course, fully manual. There is no traditional focusing ring on the lens barrel, but a knob on the right side near the mount; the minimum focusing distance is 18 meters, and a small window above the grip displays the set distance. A second knob on the left selects the internal filters: L37c (neutral), Y48 (yellow), O56 (orange), and R60 (red).

On top of the lens is a grip that also serves as a finder: this solution, later used in other extreme supertelephoto lenses (such as the Leica 1600mm f/5.6), makes locating subjects much easier — a nearly impossible task otherwise given the minuscule angle of view. Finally, on the sides are connections for the special tripod head (“Nikon Mounting AY-1”), a custom gimbal head. It weighs a massive 7.5 kg; combined with the 17.5 kg of the lens, the total weight reaches 25 kg.

Daria Ivleva, photographed at 2000mm.

The sharpness is not on the level of modern lenses, but considering that we’re talking about one of the most extreme lenses ever made 55 years ago, it was already a remarkable result for its time (and of course it was designed to resolve film, not digital sensors).

The lens hood is fixed and much shorter than those of other supertelephotos; it offers only minimal protection to the front element. The camera mount can be rotated to switch between landscape and portrait orientation.

The Nikon Mounting AY-1 head was supplied in a wooden case, while the lens itself came in its own separate, and understandably very large, suitcase. Among the accessories, it was also possible to pair this lens with teleconverters, turning it into a 2800mm f/16 or even a 4000mm f/22.

It is one of the few Nikon lenses with a white finish: only the very earliest units were gray; the rest of the production run was made with a white coating, exactly like the original 1968 prototype. It remained in production for about eight years, from 1970 to 1978 (although the exact end date is uncertain due to the lens’s rarity). Over the years, three versions were produced: the one I tested, marked “Reflex-Nikkor-C,” is the second version, manufactured from 1973 to 1975, distinguishable from the first by its improved anti-reflection coating.

Some details of the lens: at the top, the handle with built-in sight, which proved extremely useful in practical use; at the bottom, the focusing knob with its distance window and the knob for changing the built-in filters.

The Nikon 2000mm f/11 and the Nikon Df

Since this is a non-AI lens, it is an F-mount lens but not compatible with modern cameras (neither DSLR nor mirrorless), with one rare exception… the Nikon Df! This model not only features a vintage aesthetic, but also special design solutions that allow the use of all Nikon F lenses, including the non-AI lenses produced in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

In the very early years of the Nikon F-mount, which originated in 1959, the mount was nothing more than a mechanical connection between the lens and the camera: there was no communication of any kind through the bayonet, neither electronic nor mechanical. If the camera was equipped with a Photomic finder, the aperture could be “communicated” to the finder via a special prong located on the lens barrel (not on the bayonet), which latched into the finder.

The first change came with the introduction of AI lenses (Automatic Index, not “artificial intelligence”), introduced starting in 1972: these lenses had a small tab through which the lens mechanically communicated the selected aperture to the camera’s exposure meter. The camera, in turn, had a modification on the bayonet — a corresponding tab that would connect with the one on the lens.

The enormous lens cap of the 2000 mm and the Nikon Df. The front view of the lens clearly shows the mirror of the catadioptric system.

Mounting a “Non-AI” lens on a camera with the corresponding meter coupling prong would damage the camera — this applies to almost all modern Nikon DSLRs. But Nikon wanted the Df to be compatible even with lenses that are 60 or 70 years old: its coupling system can be folded back when attaching non-AI lenses. A similar modification existed for the legendary Nikon F5, one of the last professional film cameras, but only as a special service, whereas the Df includes it as standard.

(For those who want to dig deeper: Nikon USA has a nice article on this topic: Using legacy NIKKOR lenses with the Nikon Df.)

Interestingly, non-AI lenses also work on some entry-level DSLRs of the D3000 and D5000 series, because these rely entirely on modern lenses that communicate aperture electronically and include internal AF motors. These cameras lack a mechanical aperture coupler — which limits AI functionality but conversely allows mounting non-AI lenses, at least in fully manual mode.

Nikon Df, Nikon Reflex 2000mm f/11, 1/500 f/11.0, ISO 6400, tripod.

I took this portrait of Tracey from about 70 meters away; the behind-the-scenes photo gives an idea of the incredible magnification provided by the 2000 mm focal length.

Rendez-Vous

Photographing with such legendary, rare, and old lenses is always a collaborative effort, an experience made possible only by the contributions of many people. This mutual support — pooling skills, enabling new possibilities — is exactly what I love about my photographic research.

The first piece of the puzzle was meeting my friend Julian Lops. I needed a suitable camera for the 2000mm: at first I considered the Nikon Z9 with adapters, but then I thought of the Df — not only for its aesthetics and philosophy, which suit this vintage supertele better, but also because of its special mount. Julian happens to own one: I tell him about my project, and just a few days later I’m holding the Df in my hands, practicing to be ready as soon as I receive the 2000mm. The strong ISO performance of the 16-megapixel full-frame sensor will help: with no stabilization, I will need to use extremely high ISO values to avoid motion blur.

The custom-made tripod head for the 2000 mm, in its original case.

The lens mounted on the head; as you can see, the base is enormous—most likely a dedicated tripod was required.

So I set off for Vienna, carrying the necessary gear (Nikon Z5 II, Nikon Z 24–120 f/4, Sony A7R III for behind-the-scenes). With some luck, I manage two intermediate stops: the beautiful city of Graz, and then the mountains near Semmering, with their caves. In Graz, I spend the night at the hostel “Numbr 25,” a huge old workers’ dormitory at the city’s edge: long white and gray corridors, many rooms with simple wooden furniture and creaking floors, a silence broken only by the footsteps of other travelers. As a contrast to the gray concrete, the new owners have filled the hallways with paintings and artworks — new life on old walls.

This 1970s–80s atmosphere fits perfectly with the lens I am about to test: it feels like a time travel — perhaps a day in the early 70s, the very era in which Nikon unveiled this incredible project.

Nikon Df, Nikon Reflex 2000mm f/11, 1/500 f/11.0, ISO 3200, tripod

Vienna

It is a windy October Sunday when I arrive in Vienna, after taking a scenic detour through the colorful autumn mountains. Here I meet Tracey, a friend who will also model for the shots with the Nikon 2000mm tomorrow — another encounter made possible by travel. I first met her in Spain during an internship she did on a friend’s farm. We later crossed paths again on another trip, and now, years later, we meet once more in Austria. In Vienna, she guides me through the city, shows me the sights, and poses for some photos.

It is National Day — the day Austria celebrates its neutrality — and a military parade is taking place downtown. Between armored vehicles, artworks, soldiers, and the breathtaking architecture of the capital, we catch up on the past years and prepare for tomorrow’s session with the old Nikon.

Two Thousand Millimeters of Mirror

If yesterday was wind, light, and clouds, today is grey skies and light rain. Not ideal for f/11, but we make it work: I pick up Tracey and we drive half an hour to Perchtoldsdorf, where Jo Geier (www.jogeier.com), dealer of historic cameras and lenses, has opened his new showroom.

Standing in front of such a lens always leaves one speechless: at 262 mm in diameter and 594 mm in length, the Nikon 2000mm f/11 is slightly wider but shorter than the Sigma 200–500mm f/2.8, which I know well (237 mm × 726 mm). The weight is similar — 17.5 kg for the Nikon, 16 kg for the Sigma. These are truly gigantic optics that already look big in photos, but in reality are even more impressive. Among all the lenses I have tested, only one surpasses it: the Leica Apo-Telyt 1600mm f/5.6, an utterly extraordinary construction weighing over 40 kg, 42 cm in diameter (and 120 cm long), with a price tag of two million euros.

But while the Leica lens is almost a one-off — custom-made for Sheikh Saud bin Muhammed Al Thani — the Nikon was actually intended for sale, though only on request and in very limited quantities (estimates range from a few dozen to a few hundred). The original price is unknown, but today the lens sells for between €20,000 and €40,000 (Jo Geier is selling the one I tested for €20,000 — an excellent price given its superb condition), not far from a modern 600mm f/4.

The mirror on the front lens, the element that defines all catadioptric lenses.

We receive support from two members of Jo’s team: Peter and Daria. They tell me they have taken this lens out of its case only once before, and understandably handle it with extreme care given its value and rarity. Meanwhile, the rain grows heavier: going outside creates a bit of tension. We gather all available umbrellas and begin shooting, doing everything possible to keep the lens dry (it is considered robust and made almost entirely from a solid block of metal — despite lacking weather sealing, it should handle rain fairly well).

The original tripod mount proves unusable: it is enormous and would require an even larger tripod than the one we brought along. I wonder what kind of tripod people used in the 1970s — the mount is almost 20 cm in diameter and secured with three large screws, a system unknown on modern tripods. So we improvise with a sturdy 3-way head and a hexagonal base plate on the bottom of the lens.

The 2000mm focal length is — needless to say — extreme. If a 500 or 600mm supertele already feels powerful, then 2000mm is downright absurd: the angle of view is only 1.2 degrees, magnification is enormous, and handling is correspondingly difficult. The small “finder” on top of the lens proves a great help in locating subjects — an almost impossible task otherwise.

Peter and Daria try to protect the lens during our rainy shoot.

With such focal lengths, there is a lot of air between photographer and subject; the risk of atmospheric interference is high, especially in heat and humidity (fortunately not an issue today: clear, cold air). The lack of autofocus limits usability to static or slow-moving subjects. And without stabilization (the Nikon Df also lacks IBIS), one must be extremely careful to avoid vibration — always a risk at this focal length.

Between shots, I take the opportunity to get to know Jo’s team. His statement in the shop presentation had impressed me:

“We see MINT & RARE by Jo Geier as more than just a place to buy or sell cameras. It’s a meeting place for photography enthusiasts and collectors who share our team’s passion.”

That atmosphere is palpable today: a team united by passion. And conversely, it is passion that drives someone to travel ten hours just to test a lens — just as Jo and his team show passion by entrusting me with this precious optic, with which one could easily cause tens of thousands of euros in damage.

Nikon Df, Nikon Reflex 2000mm f/11, 1/1000 f/11.0, ISO 3200, tripod.

I am flying to China on Thursday, and with Daria — who is Russian but studied Chinese and lived there for some time — I talk about my upcoming trip. She shares her impressions of Chinese society, making me even more curious about the adventure that lies ahead. She also poses for a portrait: green eyes, copper-red hair, and then again the green background — an image that forms first in my mind and then through the lenses and mirrors of the 2000mm.

Finally, it is Peter’s turn — he, too, models for a day. We try to photograph between rain showers and shout to each other across the vast distances imposed by the 2000mm focal length. The sharpness does not match that of modern lenses, but considering its age and extreme construction, it is remarkable — and I find myself wondering how anyone ever achieved sharp photos with film at this focal length, without high ISO, without live view, without today’s tools.

I did not test the lens with converters at 2800mm or 4000mm — partly because I lacked compatible units, partly because the image quality would have dropped drastically since the resolution isn’t sufficient (not to mention f/22 at 4000mm, which would make it almost impossible to get a usable image).

Mirror lenses tend to produce dry, “edgy” bokeh; point highlights turn into countless rings. But with the Nikon 2000mm the focal length is so extreme that even the characteristic mirror bokeh becomes softer, sometimes almost creamy — like a watercolored background upon which our painter then creates his portrait of… Tracey, Daria, or Peter.

racey and the 2000mm, enjoying a well-deserved rest :-)

Conclusion

The Nikon Reflex 2000mm f/11 is the oldest lens and the longest focal length I have ever photographed with. It was a journey through time — starting from the idea of a Nikon engineer in the late 1960s, who could never have imagined that his creation would inspire my journey through Austria decades later.

From a technical and photographic perspective, the 2000mm is an extraordinary product for the era in which it was introduced, despite its inherent limitations. I often wondered who once owned this lens: What images were created with it? Have we seen them in books or magazines without ever knowing they were made with this lens? What remarkable experiences did its owners have? One thing is certain: you do not carry 25 kg of lens “just because” — anyone who did so must have been determined and under either significant professional pressure or driven by immense passion.

We will never know these answers — but I wanted to contribute my part by sharing, for the first time, some photos taken with this lens and satisfying at least a bit of the curiosity that I — and all those who care about the history of photography — share.